- Published on

The Craziness that Makes Xinjiang the Best Place Ever

- Authors

- Name

- Ryan K

- @thefabryk

Originally from 2012 travels, while Ryan lived in Shanghai, China

The first time I had learned about Xinjiang was when I had moved to Beijing in 2012 and my boyfriend at the time, Dave, suggested that we go there for the week-long October holiday. While I thought the offer was a little rushed, as we had just met a few weeks earlier, I knew my ache to explore China would overtake my sensibilities and I would say ‘yes’. Prior to that, Western China had no spot in my brain. It was a muddled and uncharted part of the world map, just like when we would play Sim City as a child and much of the map was grey and yet to be discovered.

But soon enough, I found myself boarding a flight to Ürümqi, the capital, still very much unknowledgeable about what was to come. Fast forward six years, many travels later, many maps now charted, yet I consider Xinjiang to be one of my favorite places on this beautiful Earth.

A flight of 5 or so hours from both Shanghai or Beijing, Xinjiang is truly China’s far-west; unlike the more popular destinations of Chengdu or Xi’an which are central in comparison. The region takes up a sixth of the mass of China, yet is so sparsely populated in comparison to China’s eastern seaboard cities. Moreover, it borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, so there are fine lines between cultures and borders which makes for heterogeneity, dissidence, and excitement at every turn.

China? Or the Middle East?

When we landed at Ürümqi airport, the most striking thing were the snow-capped mountains in the distance and the airport signs, which were trilingual in Mandarin, English, and an adapted Arabic-script known as Uyghur (which, when spoken, is a Turkic language closer to Uzbek). The Uyghurs are a Muslim ethnic minority in China that make up the majority of the population in Xinjiang region and provide the base to the true colors of the region. The food, the old sites, and the general atmosphere can be attributed to their unique culture, which isn’t ever seen ‘on the surface’ when one thinks of China and its overpowering Han majority population.

Hailing a cab from the airport, our driver himself was Uyghur, and it felt odd as we spoke to him in Mandarin, as it clearly wasn’t his native tongue (much like it wasn’t ours). As the Uyghurs have had a few isolated incidents of separatist activism in the past, there is more and more of an effort by the Chinese government to ‘integrate’ (and I say this lightly) them into modern Chinese society; this includes language training and other forms of ‘re-education’.

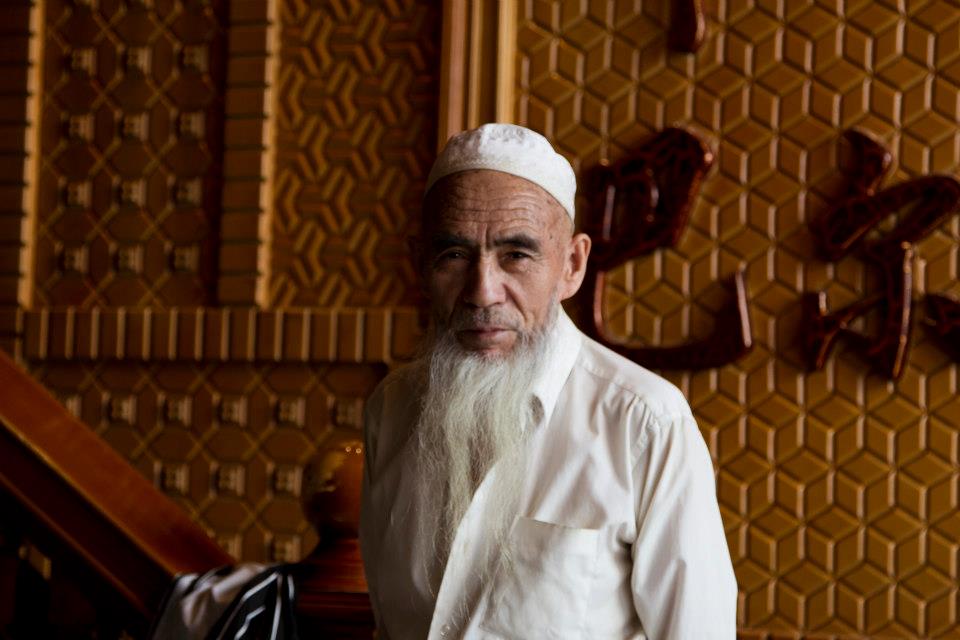

We asked him to take us to his favorite restaurant on the way to our first destination, and were blown away. Not particularly inviting from the outside, as soon as we walked in, we entered a different realm with wooden Uyghur-styled interior design, which very much resembled interior design I have seen from the Middle East. A man with this incredible beard greeted us, as he stood over this massive wok of Zhua Fan (抓饭), or Pilaf, which we later found out was rice, carrots, peppers all roasting slowly together in lamb-fat with tender chunks of lamb throughout. With the guidance of our cab driver, we ordered Zhua Fan along with some warm bread stuffed with lamb, a sour yogurt with local raisins, and some cardamom-infused tea to top it off. At that moment, I could not believe that I was in China. We were not in Beijing anymore, and I was thrilled.

Zhua Fan or Pilaf

Zhua Fan or Pilaf

Uyghur Man at Restaurant

Uyghur Man at Restaurant

Finding Inner Peace in the Sublime Tianshan Mountain’s Heavenly Lake

The ride to the Heavenly Lake of Tianshan was less than an hour’s drive from Urumqi in the nearby mountains. A strikingly blue lake, it is dotted by a buddhist temple on one side and a taoist on the other, a reflection of the diversity and co-existence in the region for centuries and millenia. Avoiding the tourists, we got onto the premises and veered right, hiking towards a set of yurts, big domed tents that I had never actually seen in person. Arriving about fifteen minutes later, we met our second ethnic minority of the day, Kazakhs, who were running a home-stay. We would be sleeping in one of those yurts for the next two nights, eating local food, and exploring the vast nature of the Tianshan mountains. After a few pricing negotiations in our non-native tongues, we moved into our home. For two people, this place was enormous. The floor was lined with carpets, and the center held a furnace that we would have to feed during the nights to stay warm. Over the next two nights and days, we back-bushed over the hills and mountains surrounding the lake; a never-ending playground for the nature lover, we explored the buddhist and taoist temples, we ate more lamb, we huddled really close at night to get through the autumn cold, and we finally were reminded what stars were after being in the light polluted city of Beijing for so long.

Kazakh children at Heavenly Lake

Kazakh children at Heavenly Lake

Inside of our yurt

Inside of our yurt

Our neighborhood

Our neighborhood

Making new friends and eating a whole chicken in dusty, deserty Turpan

Two days stretched out relatively slowly, but eventually the time came to depart. Not wanting to leave the life we were living at the Heavenly Lake, but ready to see the rest of what Xinjiang had to offer, we hopped in a car back to Urumqi to take an onward bus to Turpan, a completely different terrain of dry desert where much of the grapes of the region come from. When we were about to board a bus, we were approached by two young looking Han guys and they mentioned they were driving to Turpan, asking if we wanted to join them for a meager fee. With a bit of hesitation, we gave in and were off into the dusty desert city on the edge of the Tarim Basin. The road trip with the guys ended up being fun and before we knew it, we were friends with the two of them. Although they appeared to be Han, they were part of another ethnic minority group known as the Hui, another Islam-practicing group that appears to be more integrated into Chinese society than the Uyghurs. When we arrived in Turpan towards the evening, we ended up at a restaurant with them. That was my first experience of Dapanji (大盘鸡 literally, ‘big plate of chicken’). As the name suggests, it is a stew of full chicken (all parts could be spotted) with potatoes and peppers. As the meal gets consumed the waiter comes out and adds thick noodles on top. I clearly remember my stomach not being so hot at that time (the overwhelming amount of lamb and carbs wasn’t creating lots of movement), but I prevailed and devoured the spicy chicken..feet and all. After dinner, we took a walk around the city, hit up a bar, sat under grape trellises and discussed our cultural differences as well as the topics of virginity and sex. Just a few months prior, I was yearning to leave the US and explore this world, and then at that moment there I was in the center of Asia speaking in Chinese about taboo topics.

With only one night in Turpan, the next day involved exploring the dry grape fields, the unique raisin-drying mausoleums (they looked like crypts), the markets in Turpan, and the old ruins dating back to 1st century BC. Feeling a bit rushed, our friends from Turpan dropped us off at the train station and we were about to make the 36-hour journey west to Kashgar.

A day-and-a-half train ride that wasn’t as bad as it sounds

For anyone who has taken a train journey in China, they are not for the faint-hearted. The squat toilets are often times a natural disaster (how people aim for the walls still boggles me?!) and the triple berth beds are a nightmare trying to ascend or descend. But when you have 36 hours to kill, it forces you to make friends with the people around you. Before we knew it, we were playing a chinese card game with a little girl, sharing raisins and dates with the old man across the way, and even playing the guitar we had brought with us. We looked up tabs for Chinese songs and attempted those to make everyone feel included. Somehow everyone knew the words to “Take Me Home, Country Roads” by John Denver, so that made an appearance a few times throughout the journey.

One person we had met was an ethnic Uyghur man, Kahar, of about 27 or so. He told us his story about how he proposed to a woman from Kashgar several years earlier, but moved to Urumqi to make some money for the wedding. He hadn’t been back to see the woman or to Kashgar in general in the past four years, so this was his opportunity to head back. That is the definition of a long-distance relationship.

The time passed relatively quickly and the endless display of the Gobi desert lulled me into deep sleeps that I didn’t think were possible on a creaky Chinese train. Before we knew it, we were pulling into Kashgar.

Entering the true magic of Kashgar

Getting off the train, Kashgar appears to be like any other second- or third-tier Chinese city. There are lots of mass-produced, yet weathered high rises that provide homes for the countless numbers of citizens, big streets that aren’t designed for people, military propaganda, and a general feeling of relentless hustle and bustle that I learned to accept about China. But just a short walk away from the station, the atmosphere begins to change. The high rises fade into much smaller, but ample buildings with reddish-brown brick facades and arched entryways seen commonly on Islamic-style architecture, the roads meander into alleyways that are either filled with sun light or are completely dark due to the shadowing of the buildings, and things seem to slow down a bit; children are playing in the streets and workers, while working, are doing so at a much more leisurely pace. Continuing our walk, we enter bazaars filled with vendors selling raisins, dates, and nuts along with knives and leather products, commodities very famous to the region. Unlike other parts we had visited so far, it was rare to find a stereotypical-looking Han Chinese, as the vast majority of inhabitants in Kashgar were Uyghur. The sounds around the city reflected the cultural change too, with mosques blaring call to prayers and Uyghur language heard everywhere.

That night, despite our friend Kahar needing to tend to his long-lost fiancé, he still put our interests ahead and showed us a good time. We ate solely Uyghur food and the highlight of the night was heading over to a local Uyghur dance club. The most striking difference was the way dancing proceeded throughout the night. As the songs came on, only men would come up to the dance floor and dance with each other in a sort of swooping movement as they moved around the dance floor greeting the other men. Following this, they would sit down and women would come up and do the same. At only one point during the night, the opposite sexes would exchange a dance together. All the while, most people were drinking, suggesting that the Islam that Uyghurs practice is much more liberal than some of the other ones around the world.

We checked in at our hostel, which was an old Uyghur-style house with a courtyard and got some much needed shower-time and rest in. The next morning we checked out the Old City, which features some of the Uyghur’s truly old buildings and architecture. The winding roads and vibe was something out of the Kite Runner (which was actually filmed there) and nothing like I had ever seen in China. Buildings made of mud and brick were certainly weathering and crumbling, but the stark cultural differences between the Uyghurs and the rest of China were further made apparent by this walk. It was a little upsetting to see that China’s relentless development was encroaching on this sacred space and I sadly wondered whether in a decade the Old City of Kashgar would even be there anymore.

The mysterious and farthest west city of China, Tashkurgan

As our time was short in Xinjiang, we moved around quite quickly, and with that we left for the Westernmost city (or town) of Tashkurgan. The drive looked short, but since we were moving into the Pamir mountains, it became anything but. The mini-bus we took was well over-capacity (as was always common when traveling in China) and filled with diverse faces of foreigners, ethnic Tajiks, Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Hans; another instance of what makes this part of the world so beautiful and diverse. We bumped along for four to five hours on questionable roads until we pulled into the town of Tashkurgan.

Tashkurgan lay just on the other side of the Pamir mountain range from Tajikistan and a small strip of Afghanistan. Unlike the other cities we had been to prior, Tashkurgan, was majority ethnic Tajik; and the look of its citizens made it clear we were somewhere unique. The women wore tall and intricately decorated hats. Many of the men were dressed up as in clothes made for heavy manual work. The faces were more European than Chinese, and many of the eyes I saw were bluer than mine.

After settling down at our hostel ran by a young Han couple who had escaped the hustle and bustle of the Eastern Seaboard cities, we set out on foot to see Tashkurgan. We sat down in a dimly lit restaurant and against our will forced down some more lamb and some laghman, or noodles with meat and vegetables. The lamb-heavy and starchy cuisine was admittedly beginning to bring our energy levels down. At a table juxtaposed to us was a woman with her tall hat and her young son. After a few minutes, the son approached us and began striking up a conversation in Mandarin. His name was XiangGang or Hong Kong in Mandarin, born on the day Great Britain gave away control of Hong Kong. He gave us his phone number and told us to call him if we needed anything while in Tashkurgan, something we would take advantage of the next day.

As the sun began to set, which was extremely late in Tashkurgan as all of China ran under Beijing time and Tashkurgan was one of the furthest possible points west, we hiked up into the Stone Fort, which seemed untouched and unexcavated, a rare sight in China. It was surreal watching the sun setting over the Pamir mountain range with absolutely no sounds around us in the place highly dominated by nature.

The next day, we decided to give XiangGang a call and see what he was up to during the day. Turns out a single phone call would afford us the opportunity of getting to visit his village, which was on the way back to Kashgar. We explored the dusty town for much of the morning, bought some little gifts, and met XiangGang at a corner, where he picked us up in his family car. A few minutes later, we were walking through his village with houses far and few and made of stone. We met his siblings and talked through XiangGang to his mom and dad. XiangGang seemed to be their lingual connection to the outside China world. He took us into his grandmother’s house, an incredible woman with wrinkles containing decades of history; the true matriarch and leader of the family. He showed us the farms and fields his mother and father worked in, with the picturesque mountains as a backdrop.

Before heading on our way, we sat down to meal in the grandmothers home consisting of more meat, bread, and an interesting sour yogurt or milk. While the hospitality was the kindest gesture, we knew from the first sip of the yogurt, that the bacteria of our microbiome were not well equipped to handle it, but we sipped on showing our appreciation for the afternoon. After relentlessly thanking the family in the few words of the local language we had picked up, we were on our way back in the direction of Kashgar. XiangGang negotiated with a random car that went by in his native Sarikoli (the language spoken by Tajiks in China) and they spoke back in Kyrgyz; how anything was decided is beyond me, but we got in and were on our way.

A night of food poisoning next to the unreal Karakul Lake

The car rolled on halfway to Kashgar, with only a few words muttered here and there with our drivers, who only spoke Kyrgyz. Fortunately, we were dropped off at our destination, Karakul Lake, just as it was getting dark. We found a Kyrgyz family house to stay in for the evening and as we sat down to another homemade, our stomachs began to feel the true effects of the milk or yogurt from earlier in the day. Forcing the dinner down, we had to excuse ourselves a little bit earlier and lie down in the room we would be sleeping in, heated by a fire.

We woke up suddenly during the night with an urge to use the bathroom. In this part of the world, bathrooms resemble nothing like we are used to. Unable to hold it in any longer, we forced ourselves out of the house and over to a pit covered with wooden slabs. Squatting over the slabs, we exploded in agony, but momentarily forgot the food poisoned state we were in when we looked up and were greeted with billions of stars, the clearest I had ever seen in a lifetime, bright enough to even illuminate the whole lake in front of us. I felt overwhelmed by the universe’s beauty, until I remembered my pants were down and I was shitting my brains out in the open.

Feeling better the next morning, we walked around the lake and met some young Kyrgyz people, everyone inviting us into their homes to have a conversation and some tea. There was nothing but hospitality and kindness in this restive region.

Leaving my favorite place on Earth behind me, for now

We made it back to Kashgar for one more night before flying back to Urumqi and then back to Beijing. As I landed back in the congestion in Beijing, I couldn’t believe how much I had fallen in love with Xinjiang. The variety of the landscapes and climates that made up Xinjiang was only one small reason why it was so beautiful. The people were the main reason. Despite the cultural differences in a region controlled by greater China, each ethnic group’s identity remained heavily distinct from the others’. The mix of languages, rituals, food, and appearances make every corner of Xinjiang a drastically different place from the last. Despite the restive nature of the region and the clashing between groups, the kindness and hospitality remained a constant quality of all the people.

As we enter an ever-changing era of China, I only hope that each of these cultures can continue to live by their identities and values and continue to co-exist among one another, for a homogenous Xinjiang just isn’t Xinjiang.